Give Middle Housing a shot!

Matt Hutchins’ comprehensive discussion, at Medium, of the Washington state Model Code for Middle Housing and how we can have it produce more housing in line with HB1110.

In HB 1110, the State Legislature read the will of the people and demanded that we tackle the housing crisis more proactively by allowing Middle Housing in most cities and towns. Washington State Department of Commerce has created a basic zoning template that supersedes local code if town planners balk at updating their own code to comply. The draft version of that Middle Housing Model Code is out for comment (comment here by December 6th!). I have analyzed the real world implications of how it would regulate new housing and how we can tweak it to better support the creation of townhouses, flats, and infill development.

Here are my recommendations:

1. Allow Middle Housing to be larger than single family houses: more lot coverage, smaller setbacks, and make them taller.

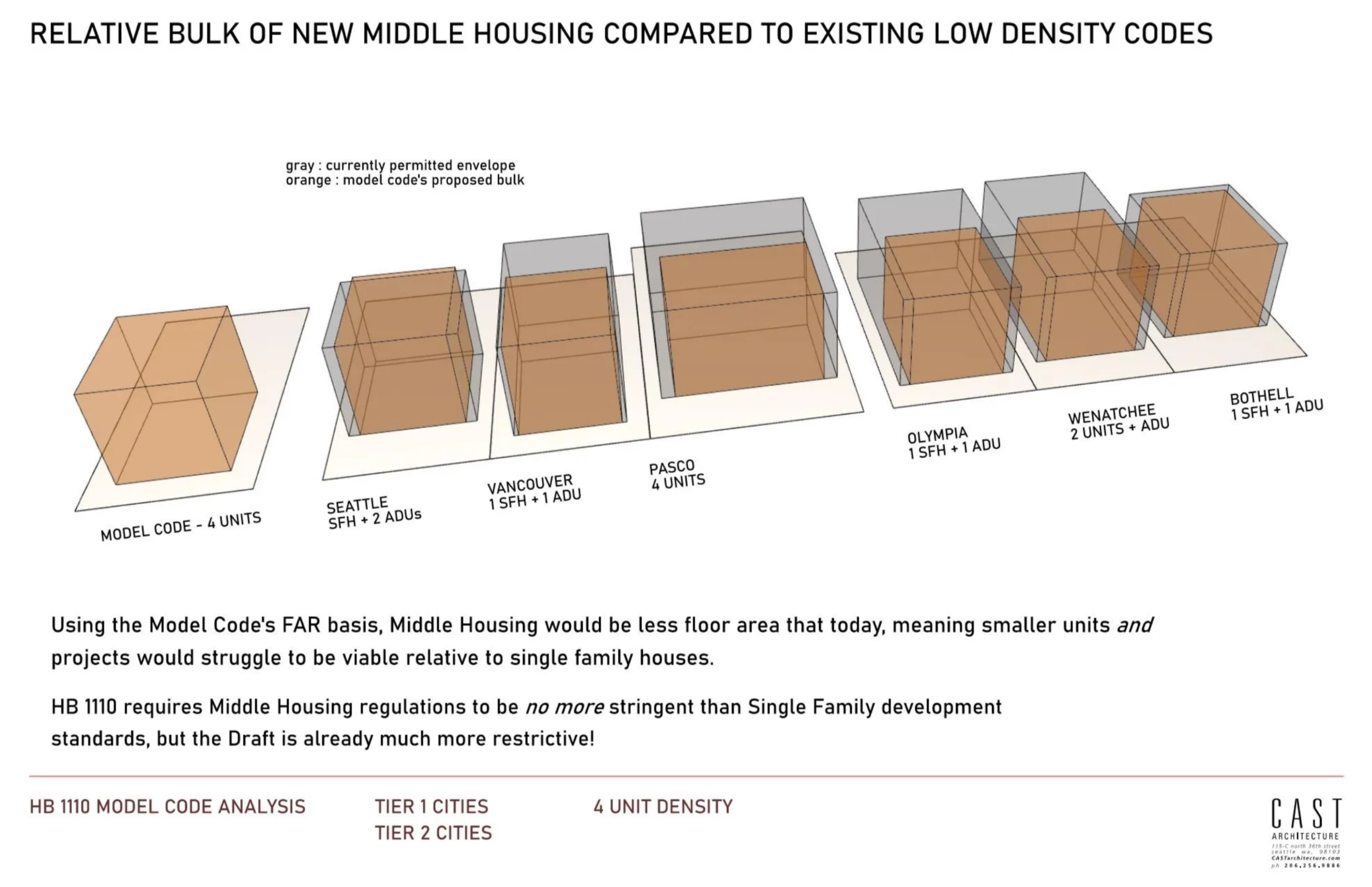

Diagram of current allowable single-family building sizes in 6 cities to illustrate that the Model Code’s Floor Area Ratio system is actually more restrictive.

It seems like an obvious point that the bulk of a building or buildings for up to 2, 4 or 6 households might be larger than one with just a single household, but a close look at some of the cities governed by this new legislation reveals that the draft code is MORE restrictive than current codes. It would effectively be a downzone in structure size in order to house more people. That isn’t a good trade, and for all the proof that Middle Housing has wide ranging benefits, we should have a code that supports it.

Middle housing is not just a bridge between the densities of single-family neighborhoods and denser areas, it is also a incremental increase in size between those building types.

2. Measure lot coverage, not FAR

There is a policy conversation about two methods for measuring building size: 1) lot coverage X height vs. 2) lot size X Floor Area Ratio. The draft code uses FAR for Tier 1 and 2 cities (the larger cities and the municipalities around them), and Lot Coverage for Tier 3 cities (smaller cities).

In the six Tier 1/Tier 2 cities I picked to analyze, five use lot coverage not FAR. The model code should follow suite. It is easy to implement, understand and compare apples to apples to existing codes.

Diagram of small cities buildable footprint illustrates how extra flexibility in lot coverage will translate to new housing for those communities.

Meanwhile Tier 3 cities, the code uses lot coverage to provide flexibility for how to develop successful infill housing, because lot coverage isn’t the critical threshold, the market is. I think this part of the Model Code will be actually be good for many smaller jurisdictions that are struggling with housing cost and access.

3. Set thresholds by looking at what can be feasibly built, not what might be politically expedient.

Illustration of all the new building types and whether they would be viable under the draft Model Code for typical lot sizes.

There is often a disconnect between how planners see development standards and how developers implement them. But ground truthing the code, when it is a draft, to understand the inevitable determinative impacts on the housing types that will get built, is the key to making the good development we want to see also the easiest to build.

Using a typical 5000 sf parcel zoned under the new code for 4 units, applying the FAR, we can build 4000sf. It becomes immediately apparent that many of the housing types we’re hoping for will never materialize and other types are going to yield less that then maximum number of units. Of the six types, I would expect the only feasible project is three townhomes. It is unlikely we’d generate very many 1000sf townhouses, 1200 sf triplex units or courtyard apartment buildings under the added cost of the IBC compliance.

The FAR needs to be up between 1 and 1.2 before we’d see the fourth townhome, or an apartment building.

4. Lean into making the most efficient and affordable housing form (small apartment buildings) the default infill Middle Housing type.

Our Spokane Six on the left works today, but wouldn’t be viable under the draft Model Code. This illustration shows that it would need to be 21% smaller.

Small apartment buildings have significant headwinds when it comes to financing, construction and operation. They also are the greenest, most efficient, context friendly and often least expensive forms of housing. They are also the best for preserving usable open space and landscape for large trees. They are the lowest common denominator building block for tackling the housing crisis. If the code works for those, then the other forms, like ownership townhouses, will work too.

When we tested our recent Spokane Grand sixplex, using the new Model Code, we discovered that we’d have to reduce the size by 21%, loose one of the porches, and downgrade the units from family friendly two bedrooms to one bedrooms. The pro forma for the development fell apart. If it can’t work in Spokane, with low land cost, reasonable construction cost, steadily climbing rents, there is very little chance these buildings would be viable in Puget Sound or other Tier 1 and 2 cities.

Without zoning incentives to build apartments, the market will continue to underproduce less expensive rental housing, even if we see some new ownership townhomes.

5. Reduce parking minimums.

Parking is always the cart that drives the horse. We have a housing problem not a parking problem.

So much has already be said and written about the high price of parking mandates, so I’m going to appeal to pure geometry.

On residential lots, designing for parking is step 1, before you even start to conceive of a building. For a sixplex on an alley, where parking is required, one space per unit arranged along the alley would require a lot width 56' feet minimum, which is wider than most urban lots. In order to provide the parking, much of the back yard is overtaken with pavement, more than 1/3rd of the site, lessening the quality of life for residents, creating stormwater issues and additional costs.

Without an alley, it is always worse; more than half of our typical lot is parking or driveway.

6. Regulating aesthetics on small neighborhood buildings is unnecessary micromanagement.

Strike this section. Or don’t. It is really so milquetoast that compliance isn’t an issue, but there will be lots of overlap/conflict with local codes that do regulate these simple aesthetics. Most townhouses are less that 20 feet wide — does a building’s design need to change every time there is a door? It is so fussy. In the interest of less bureaucracy, we should stamp out regulatory creep preemptively.

A Model Code that works.

The State’s Model Code is an opportunity to create a baseline for Middle Housing but it has to work. And this draft code would be so much more effective if it wasn’t second guessing its own mandate.

A final Model Code based on incremental increases of size over current single family structures, lot coverage not FAR, without parking minimums and design prescriptions, which allows builders the flexibility the make the homes people need, is the right direction forward for a statewide standard.